A clean energy infrastructure plan for the GGRF

California’s cap-and-trade program generates roughly $7-8 billion annually, of which $4-5 billion is deposited into the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) to support the state’s climate goals. However, there is evidence that current GGRF investments are underperforming, with multiple programs requiring thousands of dollars to reduce one ton of carbon emissions. Identifying opportunities for leverage - where $1 of public investment can generate a 3x, 4x, 5x or more improvement on key priorities such as residential rate reductions, clean energy deployment, climate resilience, and similar - could significantly improve the overall performance of the portfolio.

This blog highlights one such opportunity: dedicating a portion of annual GGRF revenues into a revolving clean energy infrastructure fund. In comparison to traditional grantmaking, low-cost loans, credit support and recoverable grants allow an initial public investment to be recouped and redeployed many times over. This reduces pressure on the state budget and can deliver greater savings to ratepayers than other methods by permanently reducing the total cost of the energy system. A revolving fund can also leverage substantial amounts of private capital to increase the total impact of a public investment strategy. For example, a 20% GGRF allocation today could total $5B in 2030, which if revolved on a conservative schedule could total $25B by 2045 – unlocking hundreds of billions in aligned private capital.

By targeting investments at high priority infrastructure, such as transmission, the fund can have the catalytic effect of unlocking gigawatts of new clean generation at low-cost. Over time, this model of focused, leveraged public investment could be extended to other key areas of climate infrastructure. And when paired with the state's evolving strategies to accelerate project development timelines, a revolving fund helps substantiate a climate agenda that can deliver at scale and on time. If these strategic investments aren’t made soon, it is difficult to see the state keeping on-track towards its climate goals. For more information, please contact Dan Adler (dan@netzerocalifornia.org) and Sam Uden (sam@netzerocalifornia.org).

***

Cap-and-trade is a central pillar in California’s climate strategy, imposing a declining annual emissions cap on regulated entities such as power plants, industrial facilities and fuel producers. One key feature of the program are the allowance auctions, which since 2013 have generated over $50B for appropriation by the Legislature and Administration in support of the state's climate goals.

Of this total amount, about 40%, or $20B, has been rebated to consumers via an annual payment known as the California Climate Credit. In contrast, about 60%, or $30B, has been deposited into the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) for investment in climate programs, including primarily High-Speed Rail ($7.4B), Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities ($5.1B), and various Transit ($3.9B) programs, each of which receive continuous allocations based upon SB 862 (2014). In recent years, the CA Climate Credit has totaled $2-3B annually while the GGRF has totaled $4-5B (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Summary of GGRF and California Climate Credit proceeds over time. Source: CARB.

In the face of recent attacks from the Trump administration, California's leadership has reaffirmed its commitment to the cap-and-trade program past 2030. Given the declining federal financial support, the expenditure of state revenues and in particular the GGRF will play an increasingly important role in financing California’s climate ambitions.

There is growing interest from policymakers in the potential for alternative infrastructure financing and development models to reduce rates, increase pace and support the state’s aggressive climate goals. In this blog, we outline a potential clean energy infrastructure plan for a modest portion of GGRF, sufficient to make a material impact on the state’s clean energy infrastructure investment challenges while preserving the significant majority of the Fund for other current and emerging priorities.

Estimating the state’s total clean energy infrastructure need

California’s ambition to achieve 40% emissions reductions by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2045 requires a substantial expansion in clean energy assets, including new generation (solar, wind, geothermal, etc.), energy storage, and electrical distribution and transmission infrastructure.

For context, we estimate the total capital expenditure needed to achieve the state’s clean energy goals. We rely on existing state plans, including CEC's SB 100 Report, CAISO’s 20-Year Outlook, and CPUC's Distribution Resources Plan, emphasizing the conservative nature of the estimate given an exclusion of inflation, cost of capital, supply chain constraints, and similar factors in the source data. Overall, we estimate that roughly $300B to $430B is needed over the next two decades to deliver a clean electricity system consistent with California’s climate goals (Figure 2). Business-as-usual financing approaches could significantly increase these estimates, particularly if assets are financed using traditional investor-owned utility approaches, which recent research from Net-Zero California and Clean Air Task Force shows can more than triple the costs ultimately paid for by consumers.

Figure 2: This chart provides an estimate of the total cost of clean energy generation and infrastructure needed for a 100% zero-carbon electricity system by 2045. The estimate is conservative as the source data excludes inflation, cost of capital, right-of-way acquisition costs, non-competitive transmission lines, potential distribution undergrounding costs for wildfire prevention, and planned behind-the-meter generation and related infrastructure costs for climate technologies such as direct air capture and electrolytic hydrogen. Source: CEC SB 100 Report (2021); CAISO 20-Year Outlook (2024); CPUC Distribution Resources Plan and General Rate Case proceedings.

Grants vs. financing for clean energy infrastructure

The expenditures summarized above highlight two evident conclusions:

To reach our climate goals, California must meet or exceed the pace of development in its best years in recent memory – and sustain that pace annually for the next two decades.

To finance these goals while maintaining affordability is a critical need. Public financing has the potential to drive down capital costs, and when paired with efforts to accelerate deployment can take key risks out of the project development process.

Traditional grants, while important and strategic if properly targeted (such as for climate resilience and early-stage technology innovation), don’t provide the same leveraging effect as loans do. Whenever a grant is made for a project that could have repaid a state program, we lose the ability to revolve that capital to the next set of projects. And when grants aren’t targeted to the risks private lenders perceive in a climate project, we miss the chance to draw private capital in once those risks are addressed.

In contrast, a revolving fund can provide low-cost loans, guarantees or recoverable grants to support the early phases of clean energy infrastructure development (often called “pre-development”), which is high-cost and uncertain for private developers. As specified development milestones are hit – such as approved environmental permits – the state could hand the project off to private financiers, recouping its investment for reuse towards another set of clean energy projects. Note that by significantly de-risking the project, private finance should be available at substantially lower-cost than it would have otherwise been absent the public investment.

A re-prioritization of GGRF expenditures should recognize that public investment, styled as low-cost, risk-tolerant debt, credit support or recoverable grants, can add a critical new tool – the ability to address key financing gaps and redeploy these funds once they are repaid.

This represents an important evolution in California’s approach to “green banking”, focused on smartly taking risks current private financing cannot cost-effectively take, and pairs well with evolving strategies to expedite infrastructure development with strong local partnerships[1]. Participating as a lender gives the state greater visibility into ongoing project performance and more ability to intervene as needed when challenges arise. By capitalizing a permanent, revolving fund with a portion of GGRF, the state could also enshrine its ability to adjust investment strategies as industries mature and new needs arise.

Potential approach to implementing a revolving fund

Electrical transmission has been identified as a high priority infrastructure need in order to reduce bottlenecks to new clean energy generation and meet the state's climate goals. In this section, we illustrate how a GGRF-capitalized revolving fund program could be applied to transmission deployment, with a specific emphasis on the early phases of project development. We assume a hypothetical scenario in which a transmission project emerges from the relevant state planning exercise and is endorsed by stakeholders in those venues. The process would unfold as follows:

A state policy process – in this case, CAISO's Transmission Planning Process – identifies the need for specific transmission assets in order to meet the state's clean energy and reliability goals. These could include competition-eligible or non-competitive, utility-owned lines.

Affordable public financing from the state’s GGRF-capitalized revolving fund would be deployed for early project development costs, de-risking and accelerating project development at a significant cost savings compared to the cost of capital from private markets;

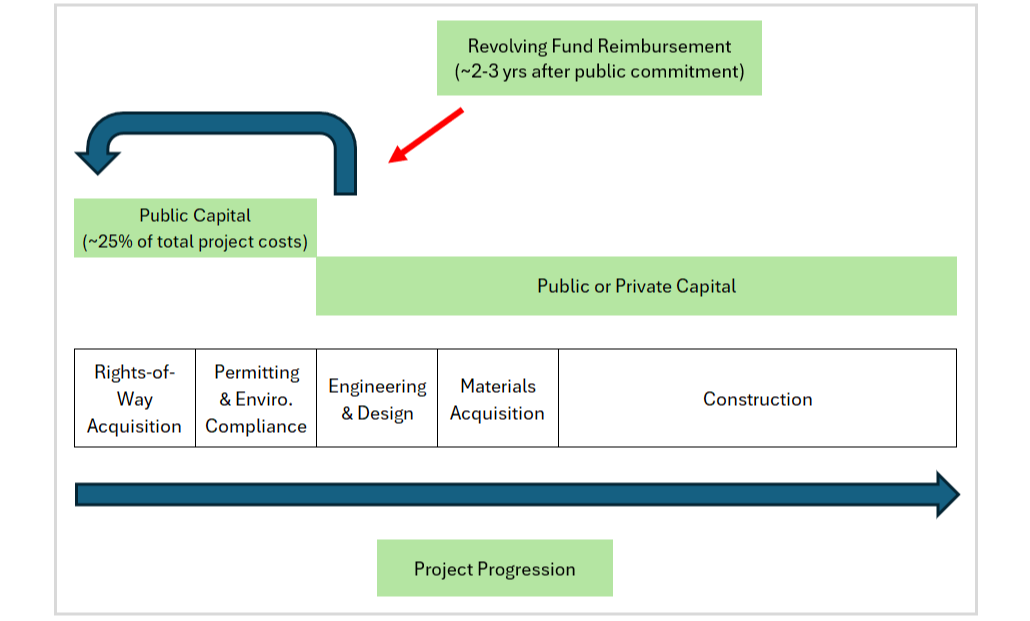

At an agreed-upon milestone, which demonstrates project viability and an accelerated path to completion, those state expenditures are “refinanced” out of the project budget, and the state is repaid[2]. If the state’s financing is concentrated on early, high-risk tasks such as rights-of-way acquisition, permitting, and environmental review, these processes typically consume approximately 25% of a project's budget and conclude in 2-3 yrs – meaning capital could be returned and redeployed at that time (Figure 3);

For competition-eligible transmission, which refers to a relatively small number of key large-scale lines that often cost over $1B per asset, further public financing for remaining project development and construction phases would maximize cost savings to consumers. This could include a local government, joint powers authority, or state agency holding legal title to the asset and refinancing it by raising revenue bonds for the remaining development phases. SB 330 (Padilla) and SB 254 (Becker) consider two different but potentially compatible options for implementing a public approach to transmission development over the short- and long-term.

For non-competitive, utility-owned lines for which there are many more projects, a revolving fund targeting early project development could be highly effective. However, given the significant amount of project de-risking that has taken place, it is reasonable for state regulators to require that (private) project finance for the remaining stages of development should utilize both cheaper equity (lower ROE) and higher proportions of debt to equity (lower-cost capital structure) – which can also help to reduce the final cost borne through rates. AB 825 (Petrie-Norris) examines the opportunity to leverage public financing in support of utility-owned transmission.

Figure 3: This diagram shows how public capital could be strategically targeted to early and high-cost development stages before being revolved (i.e. the loan or guarantee is sold by state government to institutional investors) following the achievement of specific milestones that reduced project risk.

Early-stage development challenges are significant across all transmission projects, regardless of scale, ownership, or regulatory models, and the GGRF could focus resources to address this problem. One important additional strategy that may be needed, could be to allow GGRF capital to also support a larger bond issuance by a state or local agency that is responsible for delivering one or more of the large-scale, competition-eligible transmission lines. Going forward, this model of infrastructure finance that is led by public capital in a new framework of accelerated development could support other climate infrastructure needs beyond transmission. Key opportunities include long lead-time generation, such as offshore wind and geothermal, investments in the distribution grid, and other clean technologies.

Potential scale of an infrastructure fund

A revolving fund could provide important benefits to the state in terms of energy affordability and clean energy deployment. A key question is how to capitalize the fund at a scale sufficient to capture these benefits while not jeopardizing other important GGRF priorities.

A one-time allocation sufficient to support early development of multiple key transmission lines would absorb a significant portion of the GGRF. An alternative approach would be to consider a smaller but annual allocation from GGRF such that the fund grows over time – through the combination of annual allocation and the recycling of capital – and can take on more and larger projects as the model scales.

Table 1 provides a rough estimate of how differently sized continuous allocations could be revolved – turning modest endowments into tens of billions of dollars of clean energy infrastructure investments out to 2045. For example, assuming cap-and-trade is reauthorized and GGRF averages $5 billion annually over the next five years, a 20% continuous allocation to an infrastructure fund could total $5B in 2030. If this is revolved five-times over the next 15-years, this would generate $25B in public infrastructure investments. This level of public investment could potentially leverage over $100B in additional private capital, allowing the state to substantively meet its total clean energy expenditure need at a fraction of the cost to consumers had the state relied upon private financing alone.

Table 1: This table compares alternative potential GGRF allocations to clean energy infrastructure and their revolving fund potential. The orange row shows the results highlighted in the above paragraph.

Regardless of the size of the allocation, it is critical to ensure that a state fund has sufficient capital to complete the public share of each transaction it undertakes. Only partially completing these early development objectives, running out of capital, and then becoming the cause of project delay or failure would be a negative signal to California citizens and to the market.

Conclusion

California’s climate ambition faces compounding challenges in the form of mounting costs, delayed implementation, and execution deadlines which, in infrastructure time-scales, are fast approaching. And in place of a federal administration that had been actively supportive of the state’s goals, with robust funding to support aligned public and private efforts, we are faced with open hostility and the withdrawal of committed capital support.

The state’s GGRF represents a precious resource, and the program’s reauthorization is a chance to rethink our strategy for investing these funds in more catalytic ways. Grants will continue to play a role, but capitalizing a revolving fund – and pairing it with new strategies that accelerate project development, changing the narrative on California’s ability to execute on its world-leading goals – can dramatically extend the life and impact of GGRF capital. Focusing on capital-intensive, long lead-time assets like transmission and distribution infrastructure represents an immediate need, and the model can be extended to other critical climate solutions once tangible benefits have been demonstrated.

[1] Other priorities for GGRF, as highlighted previously by Net-Zero California, include accelerated innovation and equitable climate resilience. We intend to examine these issues in future articles.

[2] There may be some benefit in keeping some portion of the state’s capital commitment in the project over the long term, e.g. to represent the ongoing public interest in the project’s development and to collaborate to overcome obstacles to execution. The state entity charged with deploying the revolving fund should be given latitude to structure investments in this manner as appropriate.