The troubled state of wildfire prevention in California

California spends billions of dollars every year on wildfire – more than ever before, and by a significant margin. Yet wildfire impacts continue to escalate – posing systemic risks to insurance markets, investor-owned utilities, ratepayers, and the state’s long-term fiscal outlook. What explains this disconnect?

The crux of the problem is that California remains locked into a largely reactive wildfire spending paradigm – one that prioritizes fighting fires, managing liability, and paying for losses after they occur, rather than investing in prevention to reduce risk upfront. A worsening climate crisis combined with the emergence of highly destructive and complex urban fires makes this, to some degree, understandable. At the same time, unless the state recalibrates its approach, communities and the environment will continue to be at risk, and the state is almost certain to be left footing an exorbitant damages tab.

In this blog, we summarize the current status of wildfire spending in California before identifying reforms that could generate new funding to increase the pace and scale of wildfire prevention. These reforms would neither compete with current suppression funding nor draw on the General Fund. Key strategies include: (i) increase the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund allocation for wildfire prevention from $200M to $500M+ for five years; (ii) establish a pay-for-success bond financing model that coordinates investor-owned utilities, insurers, and public agencies that benefit from wildfire risk reduction to finance wildfire prevention in high-risk areas, such as critical wildland-urban interface zones; and (iii) incubate and expand a sustainable wood waste bioeconomy to pay for forest treatments at scale.

These are by no means the only policies needed regarding wildfire prevention, but they are key opportunities to address the funding shortfall. Taken together, they could catalyze a shift to a prevention-first model and help the state get ahead of catastrophic wildfire risk before it’s too late.

***

California’s wildfire crisis appears to be reaching a critical inflection point. Eight of the ten largest wildfires in state history have occurred since 2018, and individual fires now carry the potential to cause hundreds of billions of dollars in damages. One or two more catastrophic events could severely limit the state’s options to ensure a viable home insurance market, solvent investor-owned utilities (IOUs), and meaningful protections and cost stability for ratepayers.

It is notable that wildfire has evolved dramatically as a public policy issue in Sacramento. Only recently, key stakeholders included environmental organizations, timber companies, and community groups. Now, it includes IOUs, global insurers and reinsurers, major institutional investors, technology companies, ratepayer advocates, air pollution control districts, and many others that are heavily engaged in policy development.

Although this has led to an explosion in the scope of wildfire policy, the fundamental need is unchanged: California needs to rapidly increase its pace and scale of wildfire prevention, including mechanical thinning and prescribed fire in forests and home hardening and defensible space in the wildland-urban interface (WUI). The barrier? We have not been able to identify reliable funding sources to support these actions at anywhere near their necessary scale.

In this blog, we summarize the current status of wildfire spending in California before analyzing three policy reforms that could feasibly unlock a significant increase in prevention activity to protect homes, communities, and the environment.

A reactive wildfire spending paradigm

It may come as a surprise to some – but there is actually not a shortage of wildfire-related spending in California, which totals tens of billions of dollars per year. The problem is that this funding is not being deployed in a manner that is targeted for reducing the risk of wildfire and related damages.

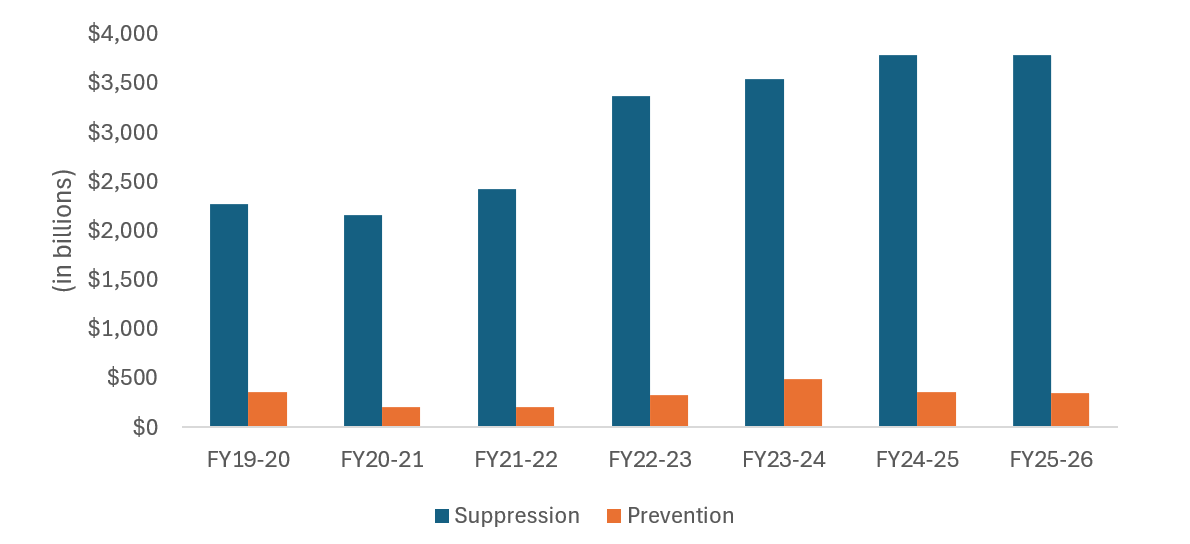

For example, state government spending on wildfire is overwhelmingly weighted towards suppression (firefighting) over prevention. In 2025-26, the state spent a total of $4.1B on wildfire, split $3.75B (or 91%) on suppression and $0.35B (or 9%) on prevention (Figure 1). Note that roughly the same allocations have been proposed in the Governor’s 2026-27 budget. Since 2019-20, annual suppression spending has increased by about $1.5B. In contrast, prevention spending – despite an increase in 2023-24 – is largely the same. A $200M continuous allocation from cap-and-invest proceeds (established in 2022-23) created some stability for prevention funding but has not meaningfully increased it.

Figure 1: Summary of state government wildfire spending based upon CAL FIRE enacted budgets and an estimate of regional (State Conservancy) annual prevention expenditures. Source: CA budget. See also: Legislative Analyst Office (2025) and Stanford (2025) for similar findings.

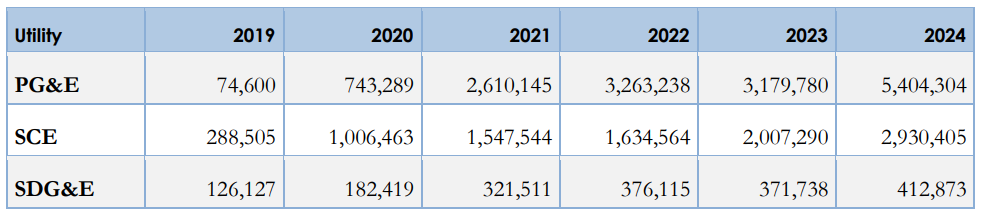

California IOUs also spend heavily on wildfire – including vegetation management, insurance, and infrastructure upgrades such as distribution line undergrounding. In 2019, this spending totaled about $500M. In 2024, it was $10B – an enormous 1900% increase over six years (Figure 2). These costs, which are passed on to ratepayers, are the main driver of what has been the state's rapidly escalating electricity costs. However, a key point to note is that the central objective of this spending is not to reduce the risk of wildfire and damages, but rather to reduce the risk that IOU electrical infrastructure is the cause of a wildfire. This is a critical distinction that in many cases drives expenditures (e.g., excessive vegetation management proximate to a distribution line while the broader landscape remains dense and fire-prone) that are optimal for IOU shareholders but not necessarily the state's policy goal to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire and related damages.

Figure 2: Summary of IOU wildfire spending, including vegetation management, insurance, and infrastructure upgrades. 2019 totals $489M. 2024 totals $8.75B. Excluded from the table is an additional approx. $1B per year that is ratepayer contribution to the Wildfire Fund. Source: CPUC.

Lastly, it is notable that insurers as well as the federal and state governments are making tens of billions of dollars in payments each year for wildfire-related damages that could have been substantially mitigated, if not avoided, with adequate prevention. For example, $22B worth of claims have been paid for the Eaton and Palisades fires alone. There are further multiple impacts that are unpaid, such as air pollution impacts. One study estimated that California's 2018 wildfire season resulted in $90B in costs related to the negative health effects (medical costs, working time loss, rising mortality) from wildfires.

A goal for wildfire prevention?

Funding actions such as suppression and ignition reduction is not necessarily a bad thing – provided there is sufficient funding for prevention. What, then, is the state's goal for wildfire prevention? And as a starting point – how significant is the direct state funding ($0.35B) for achieving this goal?

California has established goals for some, but not all, wildfire prevention actions. For forests and wildlands, the state has established clear goals – including to treat 1 million acres per year, and ideally 2.3 million acres per year, by 2025. This is estimated to cost $2-5B per year.[1] The state has not yet established similar prevention goals for the WUI – but stakeholders roughly estimate this need as the same (we can take the lower bound, i.e. $2B per year). The result is a broad estimate of California’s total annual wildfire prevention need: $4-7B. $0.35B therefore represents a very modest contribution (6-9%). IOU spending provides some prevention benefits, but it is difficult to determine how much. Overall, there is significant room for improvement on the part of the state to not only direct funding but also institute policies that drive greater shares of federal and private investment in wildfire prevention.

Three policy opportunities

Despite the current shortfall, there are multiple concrete policy opportunities that could drive game-changing funding into wildfire prevention in California. These include: (i) changes to programs under the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund; (ii) establishing regional pay-for-success wildfire prevention programs for IOUs and insurers; and (iii) incubating a sustainable wood waste bioeconomy.

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF)

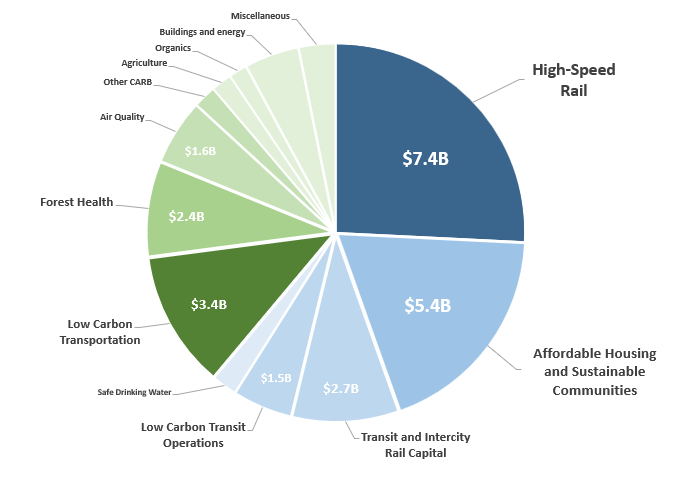

California’s cap-and-invest program is a key source of funding for multiple state programs. Since the first auction in 2013, the program has generated more than $50 billion in revenue, split roughly 40% ($20 billion) as a rebate to electricity ratepayers and 60% ($30 billion) to various environmental programs as part of the GGRF. A specific set of 'continuous' programs, including High-Speed Rail ($8B), Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities ($5B), and Transit ($4B), have received the majority of GGRF to date. The remaining funding ($12B) has been shared across roughly 90 other programs (Figure 3).

A key issue is that cap-and-invest investments have been grossly underperforming for multiple years, requiring more than $1,000 to reduce one ton of carbon emissions. By rough comparison, the state’s cap-and-invest clearing price is below $30/ton. Additionally, there is scant alignment between the current portfolio of programs and the state’s 2022 Scoping Plan – meaning current investments are generating limited support towards the state’s climate goals.

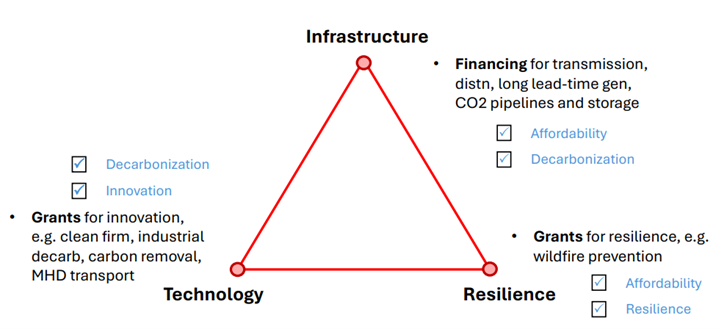

SB 840 (Limon) created a basis to recalibrate the GGRF and improve its performance. If the goal is to optimize GGRF to achieve dual goals of climate and energy affordability, ramping-up investment in wildfire prevention is a key opportunity (Figure 4). Wildfire has proven to not only be a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions – with one bad year capable of completely overwhelming climate progress in all other sectors of the economy – but is also the primary driver of the state’s record-high electricity rates. Increasing the current $200 million GGRF allocation for wildfire prevention, to a number to 2-3x this amount on a limited basis to address high-risk zones, could be justified.

Figure 4: Summarizes a potential GGRF allocation structure that prioritizes climate and energy affordability objectives, including a pillar for wildfire prevention. For more information, see: Analysis and recommendations to reallocate GGRF to achieve California's climate and energy affordability goals.

Pay-for-success model

California's current reactive wildfire spending paradigm is explained by the fact that a host of different actors are making investments primarily to serve their own priority mandates – including emergency response for public agencies, liability reduction for IOUs, and loss management for insurers. Yet, it is also the case that each of these mandates would benefit from upstream investments that reduce overall wildfire risk. If even a portion of existing wildfire-related spending could somehow be coordinated around this shared objective, it could feasibly unlock billions for wildfire prevention.

A pay-for-success bond financing model – where the “beneficiaries” of wildfire risk reduction (public agencies, IOUs, insurers) finance prevention – could be applied in this context. An example of such a model already applied in the forest sector is the Forest Resilience Bond developed by Blue Forest Conservation. In that model, generally speaking, the beneficiaries are water agencies that establish in a contract that they will pay for forest treatments in a region as the work is progressively completed (“success”) and they realize the benefits of improved water supply and quality. This contract is then purchased by investors, who provide upfront financing in exchange for being the recipient of the milestone payments. A pay-for-success program for wildfire prevention could be developed as follows:

Step 1: Identify one or more high-risk regions, such as key wildland-urban interface zones, and the stakeholders (IOUs, insurers, public agencies, others) that stand to benefit from the implementation of wildfire risk reduction in that region.

Step 2: Develop a wildfire mitigation plan and model, in coordination with the beneficiaries, identifying the various home hardening, defensible space, grid hardening, and other strategies. Estimate the financial benefits (i.e., avoided damages, avoided suppression costs, localized air quality benefits, etc.) associated with implementing the plan.

Step 3: Establish a series of legally binding contracts whereby the beneficiaries agree to make milestone payments based upon certain mitigation actions being completed and outcomes (i.e., avoided damages, avoided suppression costs, etc.) achieved.

Step 4: With these contracts in place, structure and issue a bond based upon the aggregated cash flows from the underlying contracts – thereby providing upfront financing for the overall mitigation plan. Bond issuances could be conducted in multiple tranches, from traditional institutional investors for the highest-rated bonds, to governments and philanthropies providing impact capital to absorb a sufficient portion of the risk.

A pay-for-success model in targeted wildland-urban interface settings could be one way to attract large amounts of capital and support relatively near-term implementation. Practically, a key consideration is how to implement the concept. The most efficient approach would likely be an Administration-led initiative that coordinates the main stakeholders (IOUs, insurers) and identifies various implementing actions by state agencies, as a key first step.

Sustainable bioeconomy

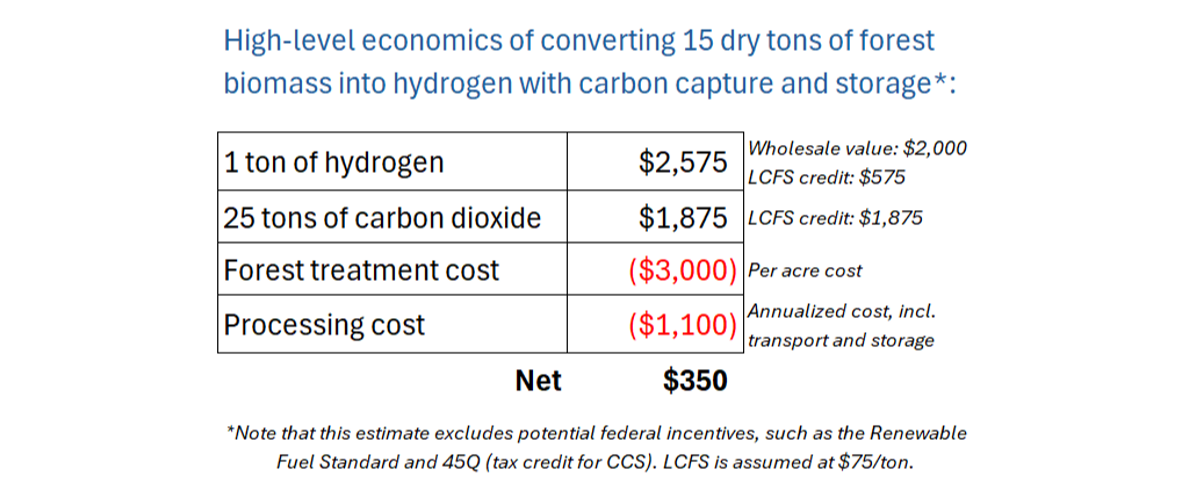

A consequence of the state’s goal to thin and manage forests at a scale of 2.3 million acres per year is that there will be an enormous build-up of small-diameter biomass waste. Collecting and converting these residues into clean products, such as renewable natural gas, hydrogen, building materials, and carbon removal, would not only generate revenue to pay for forest treatments but feasibly create tens of thousands of new jobs in advanced manufacturing in rural and tribal areas. Notably, each of these products are identified as needed at scale to achieve the state’s climate goals. The alternative – piling and burning the residues or leaving them to decay in place – causes significant carbon and air pollution while foregoing a clear opportunity to fund wildfire prevention.

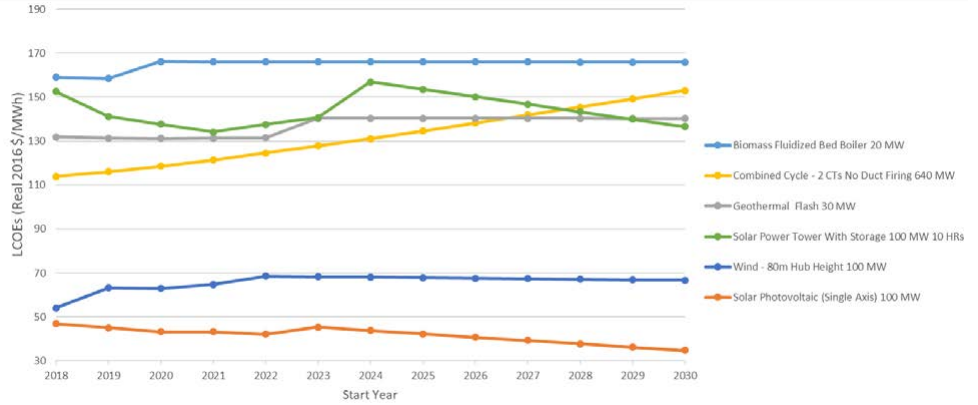

Despite there being widespread support for a sustainable forest bioeconomy – including from tribes and community groups that live in the Sierra Nevada and North Coast – the state has made almost no progress on this issue. A key challenge has been the legacy left by direct combustion, which has proven in general to be a costly and polluting biomass technology (Figure 5).

The state could establish a new vision for a sustainable forest bioeconomy that is focused on enabling technology innovation, rural and tribal economic development, and a credible long-term strategy for wildfire prevention at scale. This could be catalyzed by establishing 3-5 Biomass Innovation Parks around the state that serve as centralized hubs in order to drive regional supply chains, feedstock coordination, and public-private partnerships. Parks could be developed and managed by public agencies who attract developer tenants while the state provides support via expedited permits and supportive financing where possible. The hub model could be supported by select policy changes that remove key barriers to biomass project financing, including: (a) the inability to obtain reliable feedstock supply from public and non-industrial private lands (85% of California's forests); and (b) the inability to obtain revenue incentives for products due to a lack of guidance related to the lifecycle emissions from alternative uses of forest biomass. Collectively, these policies would create the conditions to sustainably increase the pace and scale of wildfire prevention in California (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Back-of-the-envelope techno-economic estimate of a carbon-negative hydrogen facility shows how advanced technologies have favorable economics that could cover the cost of forest treatments.

Conclusion

California has met the moment regarding wildfire in many respects – including by driving much-needed funding into suppression to protect communities and support an improved emergency response. However, the state is now in a position where it is rapidly running out of time to address the root causes of wildfire via prevention activities. One or two more catastrophic events could result in dire consequences for electricity costs, insurance availability, and potentially the state's credit rating.

Fortunately, there are policy options available to address the problem. A time-limited increase in GGRF can support urgent prevention actions in high-hazard zones. A pay-for-success program that brings together IOUs, insurers, and state government can recalibrate the tens of billions of dollars spent each year already on wildfire (but not, specifically, on key prevention actions, such as landscape-scale thinning and prescribed fire as well as home hardening). A new wood waste bioeconomy can provide a sustainable funding stream to support wildfire prevention in forests at scale. Taken together, these policies can usher in a new prevention-first wildfire and forest resilience paradigm in California.

For more information, contact Sam Uden (sam@netzerocalifornia.org).

[1] Treating one acre of forest for fuels reduction costs between $2,000 to $4,000. Assuming $2,000/acre -- 1 million acres/yr x $2,000 = $2B/yr. 2.3 million acres/yr x $2,000 = $4.6B/yr. Source: https://calmatters.org/commentary/2022/11/wildfire-prevention-biomass-climate-forest/.